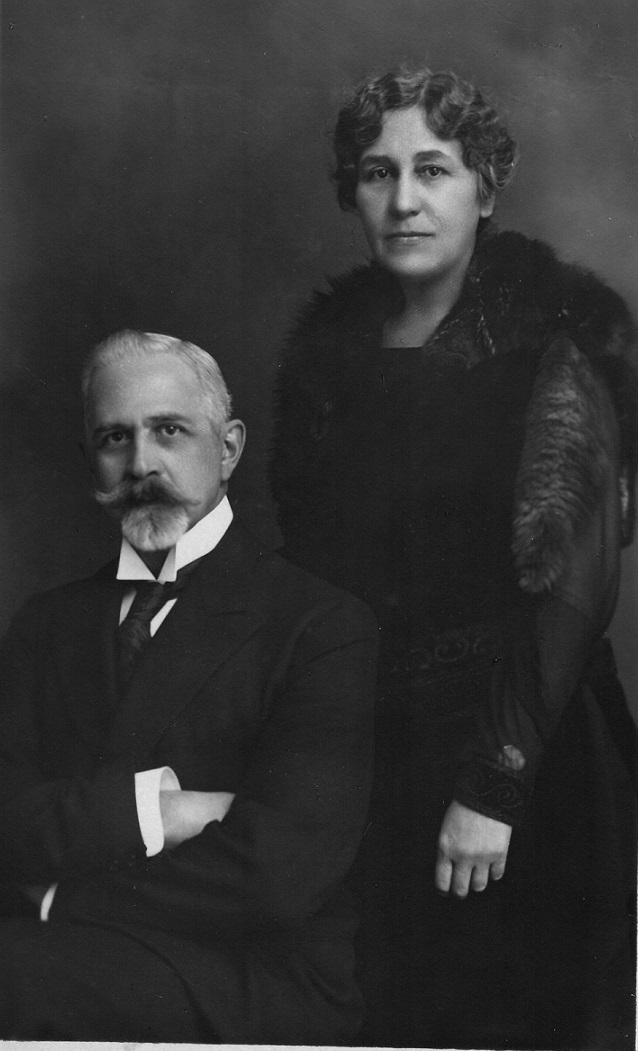

Last week we left my great-grandmother, now Catherine Yakovtsov, and her second husband, Vasily Yakovtsov (pictured together above), en route to Petrograd probably at the beginning of 1919. This week the story continues.

Catherine and Vasily made it to Petrograd but were dismayed at what the once beautiful city had become. I will let my grandmother take over the story now because she tells it so well:

“St Petersburg, now no more the capital, had been frightfully neglected. The population had decreased to half of its former (self). Neither houses nor streets were repaired, many factories had closed. In the summer, on the street where my mother lived, certainly (what had been) one of the most lively places of the city, grass had grown so high between the cobblestones that it was almost like being in the country. Every morning she watched with delight a child minding somebody’s cow that grazed under her very windows. With the almost complete absence of factory work, the air had become pure and free of smoke. She rather enjoyed this. In the winter, in the little apartment that my mother, her husband and her old maid occupied, the only heated (here I couldn’t decipher my grandmother’s writing but I assume the missing words would be ‘room was the kitchen’) and it was there that they spent most of their time.

The landlords had been deprived ownership of their buildings, there was no heating in the houses, the water pipes had burst from the cold and the water had to be fetched from a pump in a back street and carried by the tenants to their apartments. My stepfather being busy all day at his clinic, it was my mother and her maid who attended to this. Naturally, the elevator was also out of order, since it was not taken care of, they had to carry the water up to the sixth floor. If it spilled it froze and it was not an easy job to bring the day’s supply up the slippery steps. (Note: my great-grandmother would have been in her mid 50s).

At night, my stepfather returned carrying wood on his back or dragging the tied logs up the stairs. He chopped them up in the kitchen. The food question was not a very cheerful one either, for money had very little actual value and it was not easy to buy with it sufficient food to keep one from being hungry. But occasionally my stepfather’s patients paid their bills with food, which was much more welcome than paper money. Thus, unexpectedly, a pound of butter, sugar or some fish appeared on the table after many days of boiled cereal with no kind of fat milk (whole milk). It was a treat that they always shared with their less fortunate friends.

But their hardships were nothing compared with the mortal anguish that my mother went through for three years, vainly writing to us to every address she could imagine. We, on our side, had been writing with no result for she had had to move from her former apartment and, with the central disorganisation, the post office never traced her to her new dwelling. Finally, through some acquaintance who had left Russia and met my sister Claire in Constantinople, we learned where my mother lived and could at last get in touch with her.”

Their story will continue next week.